This story was originally published on Prachatai English.

Hear from Chiang Mai’s creative workers as they navigate rock-bottom wages, contract violations, and harsh working conditions, while employers cite obstacles to paying a living wage, and what makes it possible.

A barista living on 6,800 baht

Andrew, a barista in Chiang Mai, the so-called city of coffee, shares the harsh reality of working conditions in the industry. At his previous café job, he earned only 6,800 baht per month, far below the legal minimum wage.

The low pay was not due to inexperience. Andrew had previously worked at a coffee chain, where his salary had gradually increased to 15,000–16,000 baht. “It was a corporate system,” Andrew said. “I had to take tests to get promoted from junior barista to supervisor, and I became an assistant barista.

“Once I reached that position, it turned out that I had to go to help in the kitchen. From being a barista making coffee, I had to cook medium-rare steaks on the days the chef wasn’t there. This I could still accept, thinking of it as getting knowledge.

“But what I couldn’t accept, to the point that I resigned, was when I was in the assistant position, it was probably at 3 a.m. that night, they called me to clear the accounts. There was no privacy left for us to spend time resting. So I resigned.”

One day, Andrew came across a job posting for a barista at a café in the heart of Chiang Mai. Unlike the chain cafés, this one seemed genuinely serious about coffee, so he decided to give it a shot. The café manager welcomed him and promised a serious path toward becoming a successful barista.

“Actually, the salary base when they called for applications was 9,000–10,000 baht, but then they used the excuse that we were starting fresh together, so because of that the salary was low. They sold me a dream, telling me they’d send me to competitions here and there.

“At first, they said the probation period would be one month. But it seemed like I passed it within a week, and they brought me documents to sign. I thought to myself that the salary’s going up now. I’ll get it for sure. But in the end, it stayed the same, 6,800 baht. I kept working there for six months.”

Strangely, the café deducted the cost of the uniform from his paycheck every month. By the time Andrew covered his personal expenses, most of his salary was gone. He paid 4,000 baht a month on the instalments for his motorcycle, and another portion went to support his newborn in Phrae. His partner earned more than he did, but even their combined income was sometimes not enough.

“When I asked for time off, they would say that if Andrew takes leave, then who’s going to cover for him. When my child was sick and I wanted to go home, they wouldn’t let me take leave, even though I only asked for two days.”

The store manager was supposed to open the café at 6 am, but often didn’t show up until 9. That left Andrew, who arrived at 7 as the second person there, scrambling to get everything ready by the 8 am opening. When he brought it up, the manager simply said, “I forgot.”

Frustration began to build. Located near a hospital, the café required baristas to deliver coffee to hospital staff, sometimes on foot, other times using their own motorbikes. The hardest days were when the hospital ordered break sets. Andrew had to start as early as 4 or 5 am to prepare over 100 sets before the café opened.

“I went there as a barista, but I also had to create TikTok content, do marketing, and look at TikTok’s algorithm, how to get more views for a clip. The salary didn’t increase.”

Despite all this, he hesitated to leave.

“I thought of it as a phase where I had to improve myself as much as possible in exchange for a low salary like this, so I was willing to stay until my partner said a sentence that made me decide faster: paying a psychiatrist’s fees is still cheaper than staying to earn this little. My mental health at the time reached the point where I had to go my friends, asking them for advice.”

Andrew has been working at a new coffee shop for six months. This café pays fairer wages and doesn’t pile on extra, unexpected tasks.

“In another month, I’ll have a home of my own. My life has improved a lot. I just found a shop that is this good. The salary is no longer [just enough to get by] month-to-month. I even have savings. I’m lucky to have found this shop. And at this shop I don’t feel like I’m not skilled anymore. I’m skilled. Even if I don’t compete [in barista competitions], I can still compete with others. It shows that the previous shop suppressed my skills. Coming to work here, I am much more confident.”

Andrew said baristas should receive a standard salary of 15,000 baht and be granted real rights of leave as mandated by law. These improvements would give baristas a better quality of life, allowing them to develop other skills and spend more time with their families.

First job, got sued

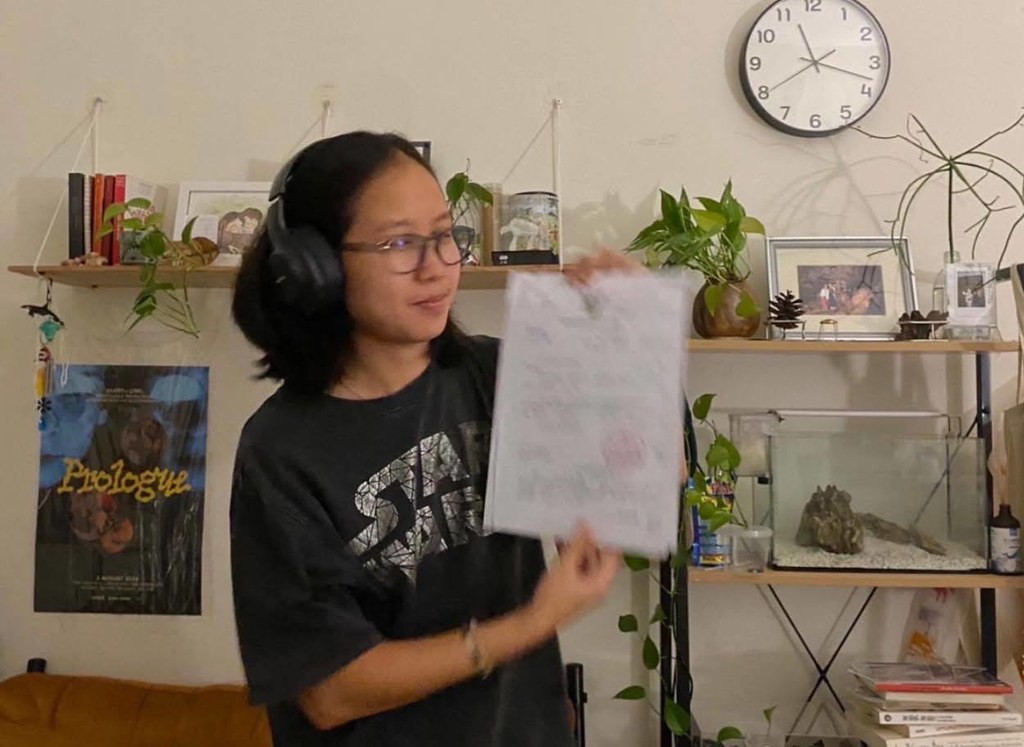

Ing, a recent graduate of Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna, began her career as an exhibition designer and has been active in Chiang Mai’s art scene. She is currently facing a defamation lawsuit filed by a former employer demanding 500,000 baht in damages.

Last year, Ing and three friends took on a project to design an exhibition based on a popular movie for a café in Chiang Dao. The film’s popularity drew Ing to the job, even though they were given just one month for both the design and installation.

Ing said that at first, it seemed like they were open-minded. But when it came time to finalize things, misunderstandings arose. They thought they had creative freedom, but the café owner required final approval.

“But the work would not be finished on time,” said Ing. “We told them that if the work had to be finalized by them like this, it wouldn’t be on time. They blamed us, saying that if we knew we couldn’t finish it on time, why did we accept the job?”

The installation period coincided with a storm. Severe flooding made it more difficult to install an outdoor exhibition and disrupted print shops and material suppliers. Ing asked the café owner to postpone the project, but they refused, adding pressure on the team.

“In the end, we delivered the work on time, but there were some points we had to adjust for them. They want to add this and that part until the work is not done and they kept refusing to pay us.”

Even after Ing and her friends made the revisions as requested, they still weren’t paid.

“It got to one point when my friend, who was always with us, posted on Facebook something like there was a news report that there was labour exploitation in this shop. And I went to comment explaining what had happened. During the storm, there was no leniency at all. We climbed up a 4-meter roof to install their work in the middle of the night.

“After that, they sued me and my friend for defamation, demanding 500,000 baht in damages, both civil and criminal cases. We were shocked. At that time, we were disheartened. But luckily, we had good friends and people around us supporting us to fight the case.

“We filed a lawsuit to claim the payment we should have got. We didn’t add anything extra because we felt it was just a payment of a few tens of thousands of baht, why couldn’t they pay? Did they have to wait for a case to be filed with the court? After that, we didn’t talk with them about anything ever again, but the exhibition continued for 2–3 months.

Ing and her friends posted explanations and wrote to the Federation of Film Directors, since the movie’s director was a member. However, the Federation could not provide support because the dispute did not directly involve the film.

“Actually, he [the film director] could have spoken up on his own, since the exhibition was dedicated to him. During the work, we still even had to interview him for the exhibition, but he didn’t speak. Silence.

“Yesterday was my graduation ceremony, and it was the same day my friend went to court. That morning, the other side [the café owner]’s lawyer called to tell us that they would agree to pay every baht but we had to withdraw the lawsuit. They could do it. They could pay. Before, out of 30,000 baht, they said that would only pay 20,000 baht. But they promoted our exhibition a lot.”

She received the payment and withdrew the lawsuit against them, but the defamation case against her is still ongoing. Currently, Ing works full-time at an international company in Chiang Mai, continuing her role as a stage and exhibition designer.

With a formal employment contract, the administrative courts and the Department of Labour Protection can assist employees free of charge when problems arise. Additionally, the company has its own legal team to support the case. This wasn’t the case when she was a freelancer.

The salary Ing receives from the company is also rarely found in Chiang Mai. She gets overtime pay, social security benefits, and a quality of life that workers deserve. Still, she is worried for others.

Her friends who are just starting out in architecture earn between 10,000 and 14,000 baht per month in Chiang Mai. Those who move to Bangkok make around 17,000 baht without a professional license. Many have left for Bangkok, Phuket, or Krabi, places with more job opportunities and faster career growth.

“In Chiang Mai, wages are cheap. Cheap like, in their hearts, won’t they let others enjoy even the basic five necessities? Even the four necessities are still hardly affordable. They can’t even buy a book or a single pair of cool 300-baht glasses. It’s a waste.”

The government’s definition of arts and culture doesn’t always align with how the younger generation sees it, which often means funding fails to reach young artists.

“I once did a survey on fresh graduates working in creative fields. These people, straight after they graduate, can only work for a short while in what they dreamed of: art, artists. After that, they find that it doesn’t allow them to survive.

“It’s sad. Their stomachs aren’t full. There’s no money to pay rent. If one day, they become baristas, they’re baristas who want to be artists.”

Tough city

“We feel that we can’t pay too little, but if we pay a lot, we don’t know if next month we’ll be able to pay that much again.”

Virinsiree ‘Ice’ Chomchoei, owner of the Some Space Gallery, said Chiang Mai relies on tourism for nearly 80% of its income. With the high season lasting only a few months each year, the profits earned during that period must also carry businesses through the low season.

“Suppose that this month we make a profit of 40,000 baht. We have to pay rent, water, and electricity bills of 10,000 baht, not including the cost of things that have to be restocked for next month and our daily expenses.

“Hiring one employee costs 9,000 baht. This month, we can pay. But next month, we earn profit of 20,000 baht because it’s the low season. What can we do? Paying rent and staff costs would already use it up.”

Virinsiree’s business goes through significant ups and downs. With such unpredictable income, she has chosen not to hire any staff and instead runs everything herself. These days, the gallery feels less like a business and more like a passion project to her.

She understands why small business owners in Chiang Mai can afford to pay their employees only between 9,000 and 12,000 baht, but she doesn’t agree with it.

“There are some people who have a profitable business model for a large-sized business but act as if it was a small-sized model. This means that the companies make hundreds of thousands of baht in profit each month, but they still pay their employees only 9,000 baht. It’s like they see others doing this, so they do it as well.”

To break what she called a ‘vicious cycle,’ she proposed that Chiang Mai diversify its sources of income.

“Chiang Mai’s economy depends too much on tourists, and we can’t stand on our own feet. People in Chiang Mai can’t go out to drink wine, can’t buy expensive clothes. What percentage of people can do that in Chiang Mai? But who goes out to spend their lives listening to music? Tourists.”

Workers’ lives matter

Originally located near Kasetsart University in Bangkok, School Coffee has been operating for over 12 years. One of the partners, Borriruk ‘Big’ Apikhantikul, didn’t want his son to grow up in a city full of stress and traffic jams. So, three years ago, he decided to move the shop to Chiang Mai, right where the coffee plantation that supplies it is located.

In Bangkok, they had four full-time employees and several part-time workers, mostly Kasetsart University students. After moving to Chiang Mai, the shop now employs five full-time staff and one part-time worker.

“If they are full-time employees, they will have a starting salary of 15,000 baht, and it increases based on experience. Right now, the employee who earns the most is at around mid-20,000 baht, depending on the month.

“This is because the issue of bonuses from sales also comes into it. For example, this month we conclude that we sell 3,000 cups of coffee, and we will divide the bonus among everyone. Secondly, if we reach our target for sales of roast coffee as planned, we will have an additional bonus to give out.

“Benefits include unlimited drinks at the shop. We want the juniors to understand and learn from the drinks they make themselves. There are mid-year holidays. Some years we close the shop for 5 to 7 days during the haze season, like a short school break.”

His philosophy: “The most important resource in the shop is the ‘people’.

“If we look back to when we first started working, the money should be enough to live on in real life, covering gas, rent, and food. The employees should have to have savings to buy clothes or whatever they need.

“We believe that people are the first factor. By making people happy, the work will naturally come out well. It has been exactly like that over the 12 years that we have been working.”

There are times in Chiang Mai when the city becomes quiet during the peak of air pollution or the flooding period, causing sales to drop drastically. Even then, School Coffee has never considered cutting employee wages to save costs.

“Like when there was a flood, the only thing we didn’t cut was their salaries. We could cut other things; we could save on other things.

“This shop wasn’t built to turn the owners into millionaires. Me and four of my friends who are co-owners, we want to create a little community of our own. During the low season, some months we might break even or make a little profit. The owners of the shop won’t earn much, but during the high season, which is so short, we can make some gains.

“When the low season arrives and it’s time to pay salaries, I always tell the team, hey, let’s all help save the costs. Let’s help each other to find new products, new drinks that can increase our income during the times we might struggle a bit. We always get suggestions from the team, so I think it’s okay. It’s fun, they’re happy, that’s enough.”

His response to employers regarding the fact that some baristas in Chiang Mai still earn below the minimum wage: “Let’s go back and think. If it was ourselves, could we survive? A single serving of food already costs 50 baht.”

“If paying fair wages makes you worry about costs, I want you to try to re-plan your business. If you’re still not ready to pay fair wages, don’t rush to open.

“If you’ve estimated that by setting up a shop here, and selling coffee at this price, you can’t pay 15,000 baht wages, I want you to re-adjust. Find a new location. Can you create a new pricing structure? So that in the end we can pay our employees properly.

“Nowadays, everyone knows that running a coffee business isn’t easy. It’s so competitive that it can make you lose. If you know that Chiang Mai’s low season will be tough, you have to factor that into your shop’s concept. If we plan well, the low season won’t be a problem.”