This article was originally published on HaRDstories.

Shouts rang out deep in a Phatthalung forest as hunters spotted their prey. A young man plunged into the undergrowth with his two hunting dogs. Others grabbed their ‘balau’ – quivers full of poisoned darts – and followed.

The monkey raced from tree to tree, trying to outrun the cries from the hunters below, but was soon struck by one of the chasing darts. Once the poison took hold, the animal crashed dead to the forest floor – dinner for the Maniq, Thailand’s last known hunter-gatherer group, who are themselves struggling to outrun the inevitable march of modernity.

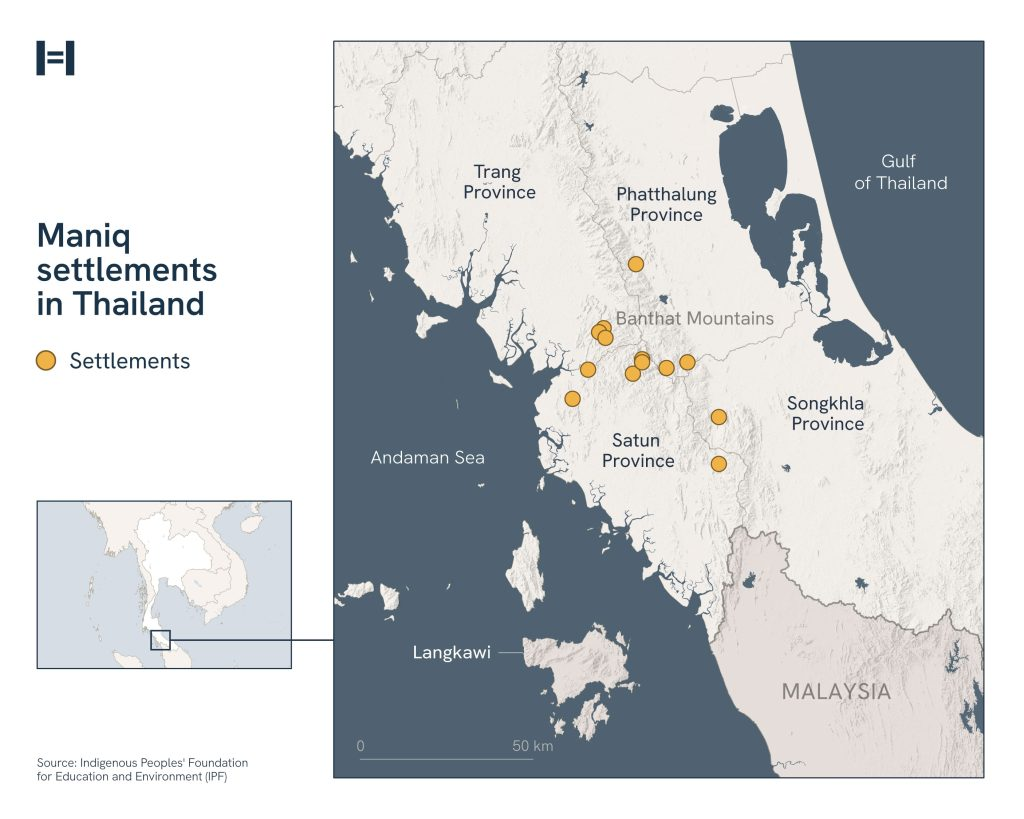

Fewer than 500 Maniq remain, according to the Indigenous Peoples’ Foundation for Education and Environment, scattered across the mountains that straddle the four southern provinces of Trang, Satun, Phatthalung, and Songkhla. The Maniq trace their lineage to the Negrito, a nomadic group that populated the tropical forests along the Malay peninsula.

Dwindling wildlife and stricter anti-poaching laws have forced the group to shred its centuries-old nomadic life. Many have settled into homesteads and enrolled their children in state schools. But their new lives rest on shaky legal ground: Thailand’s environmental laws regard the Maniq as illegal occupiers of protected forests.

The Maniq’s plight mirrors that of other indigenous groups who inhabited Thailand’s forests long before Bangkok designated them as protected areas and wildlife sanctuaries – often with no consultation. These legal barriers, often enforced through violence and evictions, effectively deny the Maniq and other ethnic minorities basic rights, such as owning the very pieces of land where they live and toil, or relying on the forests for their sustenance.

Enforcement continues – though some communities have won temporary reprieve – despite protests from local communities, rights organisations, and experts. They argue the Maniq co-exist with the forest ecosystem and that their use of natural resources sustains their lives without the environmental damage officials claim.

Hunters with almost nothing to hunt

The hunt in the Phatthalung forest was a chance for Dan Rakpabon, 18, to learn the old way of the Maniq. Dan carried the monkey’s carcass back to the makeshift settlement, which consisted of seven huts clustered in the forest. The nearest village is ten kilometers away.

Back at his hut, Dan lit a fire to roast the meat, and shared it with his neighbours. Like other Maniq men, Dan said hunting brought him joy. But there’s less to hunt now – organised poaching rings by outsiders have depleted the wildlife.

To compensate, the Maniq entered the market economy. Men became labourers in rubber plantations. Women wove baskets and bags to sell. Yet legal restrictions bar them from planting or tilling the land, even for their own use.

“We want proper houses, land to grow our own vegetables,” said Jeab Rakpabon, a Maniq woman, “shelters made from leaves like this are only temporary”.

Jeab spoke to HaRDstories while weaving a bag from pandan leaves collected in the forest. She can make four bags a day, fetching 50 baht each, or about 1.50 USD. She shares the income with other women in her weaving group.

Tom Rakpabon leads the 40-person settlement. He remembers childhood days in the jungle with his father, learning to hunt and forage. Now his community must buy nearly everything – rice, meat, vegetables – from the market. Even their names came from outsiders, Tom said, officials gave them all the same surname, Rakpabon, when they applied for national ID cards.

“I’m used to it now,” Tom said of the changes. “Nowadays I get to learn about the outside world. I went from being a shy person to having more courage to speak up. The only thing that still worries me is that the Maniq culture may disappear in the future.”

Small victory

Chalerm Phummai, director of the Wildlife Conservation Office overseeing the area, acknowledged the Maniq’s long history. They lived among these trees before the Khao Banthat Wildlife Sanctuary was established in 1975.

He said officials treat the Maniq with respect and understanding, letting them hunt in protected forests according to local custom.

But every other provision of the Wildlife Conservation and Protection Act, enacted in 2019, applies to the Maniq without exception, Chalerm said.

“Not only the Maniq people, but everyone must obey the law equally,” the official said in an interview.

Under the law, established indigenous communities on protected land can request 20-year permits to utilise and inhabit the land, subject to renewal. They must also follow strict conditions to protect the environment, he added.

Wildlife officials present the law as a compromise between indigenous rights and conservation. But it has drawn fierce opposition from indigenous communities in protected forests. They held protests and sit-ins, most notably outside Chiang Mai City Hall from March to April. That demonstration led to a Cabinet resolution suspending the law’s provisions pending consultations and amendments.

It’s a small victory for the campaigners, who have long advocated for the rights of local communities to coexist with forest lands, but the future remains murky for the Maniq hunter gatherers.

Tensions of lives in the ‘protected’ zone

A dirt road, churned into mud by weeks of rain, leads to a very different Maniq settlement. Here, in the patch of lowlands inside the Khao Banthat Wildlife Sanctuary, the local Maniq do not move about in the forests or sleep under leaf shelters. They live in permanent concrete and wood homes with plots for growing crops.

The community, Plai Klong Tong, secured permission under the 2019 law to establish long-term presence in protected areas. But the arrangement brings neither the freedom nor certainty residents sought, said Thawatchai Paksi, a local resident.

“It’s frustrating to live like this,” Thawatchai fumed. “We need permission for almost everything – even cutting down a tree or building a house.”

Thawatchai’s mother, a Maniq woman, married a local man who taught her and others to plant rubber trees and build houses. They eventually settled at what is now Plai Klong Tong. But the community lives on borrowed time – residents can only hope to be allowed to stay every 20 years.

Many families now enroll their children in local public schools, said village leader Sakda Paksi. The move helps secure a stable future for younger generations but also brings new pressures.

“When we were hunters, we didn’t have to think much,” Sakda said. “But now that our children are in school, we have to find jobs and money [to pay for the education].”

But the 2019 law bars commercial use of forest land, preventing large-scale hunting or agriculture and forcing many to become day laborers and farmhands, Sakda said. The pay is often meagre – about 100 to 300 baht per day.

From hunting to handouts

An even starker departure from the Maniq traditional way of life unfolds in Satun province, where a group of Maniq people follow a daily routine of trekking from their settlement for three kilometers to the main road. There, they sit under crude shelters, waiting for donations from passersby.

Community leader Jin Srithungwa said her group left the sanctuary’s forests because of dwindling food and scarce work.

“If nobody gives us food, it’s difficult for us,” Jin said.

A trickle of tourists on sightseeing trips stop by and give them donations throughout the day. One of them was Kritsada Inchalerm, who said he first encountered Jin’s group some time ago while driving by on this road. Intrigued by their distinct appearance, Kritsada said he stopped his car and talked with the Maniq people. Since then, he always brings goods and money when driving this route.

Like many Thais, Kritsada first learned about the Maniq from “Sagai United,” a 2004 comedy film about underdog Maniq footballers who leave their home in the forest to compete in Bangkok. Most urban audiences didn’t know the term Sagai is considered derogatory by the Maniq – it derives from a Malay word meaning “slaves.”

Many Maniq interviewed by HaRDstories said they want a legal arrangement allowing them to sustain themselves through hunting or farming rather than relying on handouts. But current restrictions on protected land make that impossible.

“I want the authorities to give us lands where we can make a living,” said Tao Khai, a village elder from another Maniq community in Satun province. “We are not savages.”

When asked about these concerns and aspirations, Chutiphong Phonwat, head of the Khao Banthat Wildlife Sanctuary, said his agency alone is not in a position to meet many of those demands. Instead, agencies like the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Social Development should work together to find land for the Maniq and offer job training, he said.

“We are not concerned about the Maniq’s traditional way of life,” Chutipong said. “They do not destroy the forest. They help us protect the forest.”

But anthropologist Apinan Thammasena said a new law on indigenous groups that took effect in September offers another solution. Under the law, communities can be designated “protected ethnic areas” where residents can use land and natural resources according to their traditional way of life, Apinan said. The legislation is far more flexible than the 2019 wildlife law many indigenous groups oppose, he noted.

While the measure would still stop short of granting legal, permanent land ownership to communities like the Maniq, the process involves collaboration between the indigenous groups and relevant authorities, which would allow the former to inhabit the forest land indefinitely, without fears of being evicted by the latter.

“The Maniq will not be granted land ownership, but they will receive rights to use the land in accordance with their traditional way of life,” Apinan explained. “Land security does not necessarily have to come in the form of ownership. It can come in the form of guaranteed, permanent rights to use the land.”

Piling hopes on education

Every morning, Duan Srimanang, 13, goes to school with other Maniq children in her village in Satun province; a worker in a nearby rubber plantation picks them up and drives them. Duan stands out – she’s in second grade while her classmates are older. She can now write her name and is learning to read, she told HaRDstories.

Efforts to integrate Maniq children into public schools have been underway for a decade. But educators and some Maniq say the attempts often fail.

Many Maniq start school late and struggle to fit in with younger classmates. Others drop out because of hardship. Dan, the young hunter, started school in Phatthalung province but quit in third grade to help his family earn a living.

“I want the young ones to go on and complete their studies,” said Dan, who now has a second job as a rubber plantation farmhand, earning 100 to 200 baht per day. The savings go to supporting his younger relatives in their education, Dan said.

His neighbour, Jeab, hopes her children will graduate and find stable jobs.

“One day my child came to me and said, ‘Today, I can write my name.’ Just hearing that made me proud,” Jeab said.

Saowanee Chailak, a teacher at a public school in Phatthalung province, said Maniq children could finish high school or even university with adequate funding from the central government and community support.

“I believe that Thailand in the future will see Maniq people doing jobs that other people do, such as teachers, nurses, police officers, and soldiers,” she said.

For now, Duan has no other ambition than doing well in school.

“I still don’t know what job I’ll be doing, but I like going to school because I have so many friends there,” she said. “When I grow up, I want to have a job and earn money so I can take care of my mother and make her comfortable and happy.”

Same laws, same challenges

The Maniq are one of 42 ethnic groups in Thailand who have come together through the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Thailand to campaign for indigenous rights and autonomy over their lands. Their latest achievement: making Thailand the fourth Southeast Asian country with laws protecting ethnic groups, after Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

But Laofang Bundidterdsakul, a lawmaker who helped draft the indigenous bill, worries the law can be superseded by existing wildlife and environmental legislation – laws that have proved a bane for many communities because of their restrictive language.

Laofang, a Hmong lawmaker with the People’s Party, said even if the Maniq secure “protected ethnic areas,” they won’t achieve the autonomy they’ve fought for. Land ownership will remain unresolved, he said. And it’s unclear whether they can access basic infrastructure, roads, electricity, water, since construction requires Forestry Department permission.

“The Maniq people will still have to live under the structure of the current laws,” he lamented.

The lawmaker said his party will continue to propose amending relevant laws that would allow the Maniq and other ethnic groups to coexist with Thailand’s protected forests, while keeping any impact on the environment to the minimum.

Back at the makeshift camp in the forest of Khao Banthat Wildlife Sanctuary, Maniq hunters distributed the food they foraged from the hunting expedition to their neighbours. The sun disappeared among the trees, its lights replaced by glows of headtorches from Duan and other children pouring over their homeworks. The adults gathered around the fire and cooked with what the men brought back from the jungle, with some ingredients bought from the market thrown in.

“This land was given to us only temporarily,” Tao Khai, the Maniq elder, said. “The Maniq want a home where we can live forever.”

Edited by Teeranai Charuvastra.

This story is a collaboration between HaRDstories and AFP, with support from the Pulitzer Center.

Nathaphob Sungkate is a feature writer from Thailand focusing on human rights issues. His work is informed by a year spent in India. Nathaphob is committed to in-depth reporting to shed light on underrepresented stories.

Luke Duggleby is a long-time Thailand based photographer. He regularly works on stories related to human rights, the environment and the impact of pollution and development on local communities.