This article was originally published on Prachatai.

Over the past year, the monarchy reform movement which began during the student-led protests of 2020 has become less prominent as activists face continued prosecution, particularly under the royal defamation law. Ultra-royalists, whose activities had been a reaction against the call for monarchy reform, appear to have shifted their focus.

Known for their extreme pro-monarchy attitudes and propensity for violence, these groups have been active since 2020. They have filed dozens of royal defamation complaints against pro-democracy activists, politicians, and ordinary citizens who criticize the status of the monarchy in Thai society and call for reform. Some ultra-royalists have also attacked pro-democracy activists and citizen journalists at protests and made death threats against student activists for criticising the monarchy.

Some ultra-royalist groups, like the Thailand Help Center for Cyberbullying Victims, have disbanded. Others have turned their focus onto migrant workers, particularly those from Myanmar. Their xenophobic social media posts, riddled with misinformation and calls for violence, appear to have provoked a wave of anti-migrant sentiment in the online space.

#UngratefulMigrants

Migration has long been a divisive issue in Thailand. The sentiment among Thais fluctuates between claiming either that workers are a crucial part of the economy, or that they are a burden on the country’s welfare system. After the February 2021 military coup in Myanmar resulted in an influx of migrants into Thailand, anti-migrant sentiment, fuelled by nationalism, appeared to surge.

Political parties proposing humanitarian aid and benefits for migrants have been attacked. The People’s Party, the main opposition party formed after the dissolution of the Move Forward Party, faced a backlash after its MP Tisana Choonhavan called in parliament for humanitarian assistance for migrants fleeing the civil war in Myanmar. The party was dubbed “the People’s Party of Myanmar” by conservatives, who accused it of prioritizing refugees over Thai citizens, while posts criticizing Tisana were widely shared on social media.

Even the Cabinet’s resolution expediting citizenship and permanent residency applications for long-term immigrants and ethnic minority children has been condemned as a betrayal of the country and opposed by ultra-royalists groups, who falsely claimed that the government was granting Thai citizenship to all migrants.

A coalition of four ultra-royalist groups under the name “Thai Mai Thon” (“Thais won’t stand for this”) has staged several protests with an anti-migrant agenda, including one against the Cabinet resolution.

Another was held on 1 February 2025. The group claimed that their protest was to counter one organized by the Myanmar community to mark the 4th anniversary of the February 2021 Myanmar military coup. However, the two groups did not clash as the migrant workers group Bright Future decided instead to file their petition with the UNHCR one day earlier to demand that the UN boycott the general election in Myanmar, which might take place this year, and to ban companies that sell weapons to the Myanmar military.

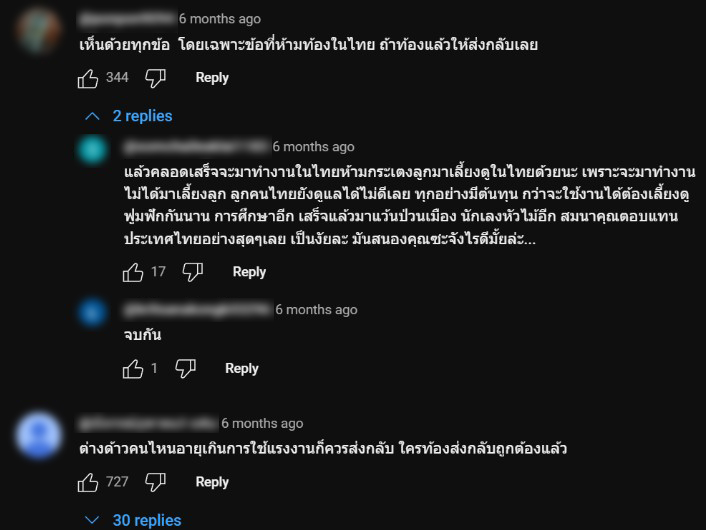

The anti-migrant groups often claim that they target only people who break the law, but their agenda is often discriminatory and hateful towards migrant workers as a group. In September 2024, right-wing activist Akkarawut Kraisisombat, known for his hardline stance against migrants, and a group of other activists attempted to petition the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a law prohibiting migrant workers from getting pregnant or giving birth in Thailand. Comments under a video clip posted by Top News backed their petition, saying that it was right to deport workers who are pregnant or “too old for labour.” One comment was that if pregnant workers are deported, they should not be allowed to bring their children back to Thailand after giving birth.

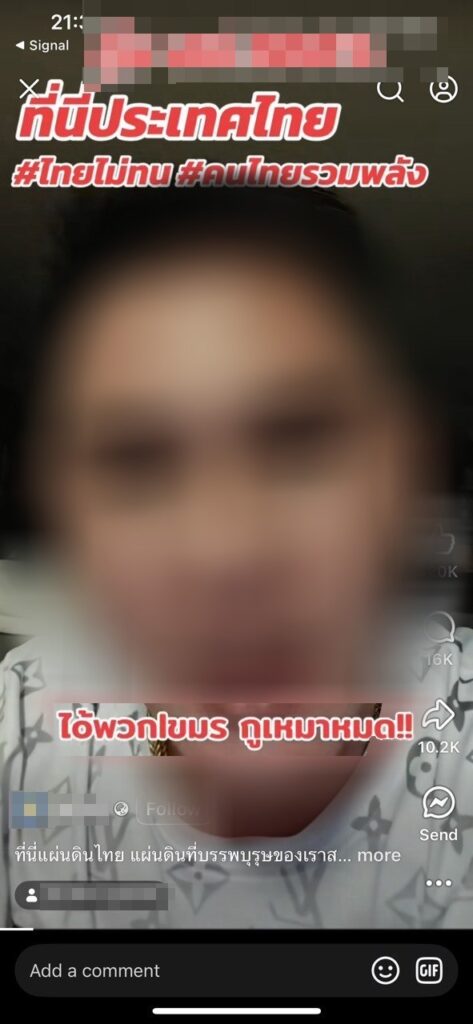

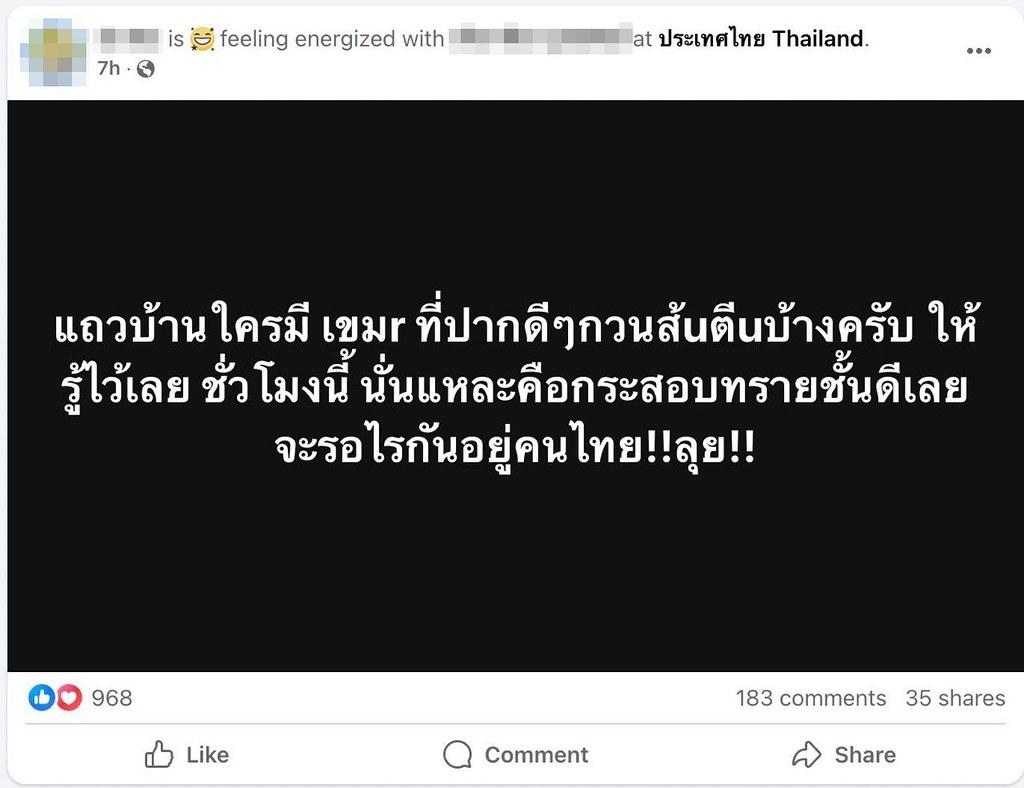

With the hashtag #ต่างด้าวเหิมเกริม (“Ungrateful migrants”), group members have threatened violence against migrant workers as retaliation for alleged gang activity and harm done against Thai nationals. They have also claimed that migrants have no right to stage protests in Thailand.

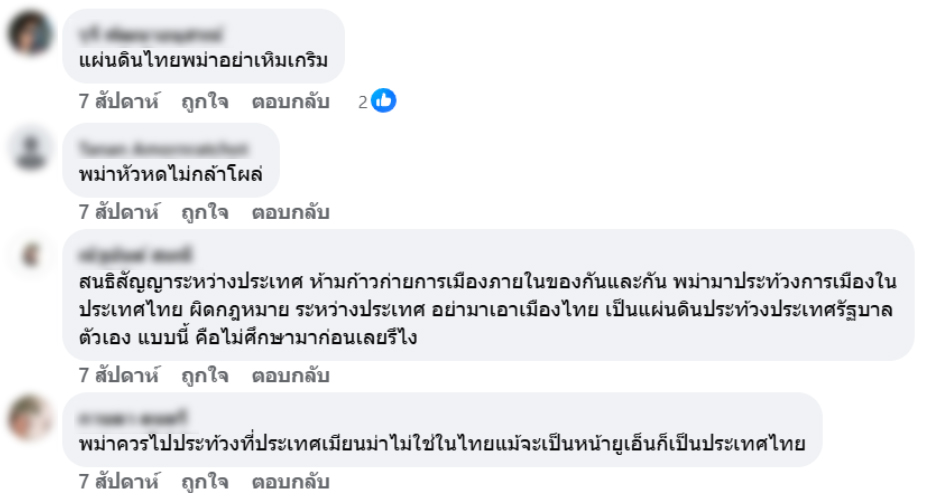

Comments under a post on the People’s Centre to Protect the Monarchy’s Facebook page echo this sentiment, with one claiming that it is against international law for foreigners to organize protests in Thailand.

This is not the only misinformation spread as part of the ultra-royalists’ campaign against migrants. There have also been posts on social media claiming that the workers were protesting to demand that minimum wage be raised to 600 – 700 baht (between US$18.5 to $21.5 per day). An account on TikTok, for example, edited a video clip of Weera Sangthong of Bright Future speaking about wages in 2022, added a People’s Party logo to it, and posted it on the platform. The clip has over 4.5 million views and has been widely reposted.

Akkarawut had also posted on Facebook his discontent, claiming that Myanmar workers are demanding a minimum wage of 600-700 baht while Thais are being paid 400 baht (about US$12).

Nantiwat Samart, former Deputy Director of the National Intelligence Agency, posted on 1 February pictures of three previous protests held by Myanmar migrants in Thailand with a caption claiming that the migrants were marching in front of the UN on a day when no protest took place involving Myanmar workers. He wrote that the migrants should all go back to Myanmar if they want to protest, so that Thais will have more jobs. He also wrote that any company who could pay should go ahead and pay migrants the 700 baht or MPs who support the migrants should be able to pay it, and that it is difficult for Thais to get paid even 400 baht.

“The workers could live. The private sector goes bankrupt and factories close. The security sector and labour should discuss it again” he wrote.

The post was shared over 12,000 times. The comments are full of hate towards migrants. Many said that the migrants were demanding more rights than they deserve, and that they should go back to their own country.

Online hate towards migrant workers has turned physical. On 5 April, Bright Future called a protest in front of the UN headquarters in Bangkok against Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, leader of the Myanmar junta, who was in Bangkok at the time for a summit on regional economic cooperation. As Weera was arriving at the venue, ultra-royalist activists were waiting and attacked him.

Among Weera’s attackers was Songchai Niamhom, leader of the ultra-royalist King Protection Group and known serial royal defamation complainant. Songchai filed a police complaint against Weera, accusing him of being part of an unlawful secret organization and inciting unrest. He claimed that the Thai Constitution does not allow foreign nationals to stage protests on Thai soil and that doing so is seditious and an interference in Thailand’s internal affairs because the protesters were calling on the UN to pressure the Thai government into following their demands. He also claimed that Weera previously joined a campaign for the repeal of the royal defamation, sedition, and anti-strike laws, (Sections 112, 116, and 117 of the Thai Criminal Code).

The claim that Weera supports the repeal of the royal defamation law appears to be a piece of misinformation often spread among ultra-royalists and their supporters, who have used protecting the monarchy as a justification for their actions. Although Weera and other members of the Bright Future group are often seen attending pro-democracy protests organised by Thai activists, their own gatherings are protests against the Myanmar junta or calls for labour rights.

It would appear that there is a growing number of netizens who share their anti-migrant sentiments, which was not the case with their previous campaign against monarchy reform. Comments under their social media posts and reports of their activities show that a number of netizens want to deny migrant workers their rights. On a TikTok video posted by Akkarawut, one comment said that migrant children educated in Thailand and who receive citizenship are “a growing virus to wipe out all Thailand’s laws.”

At a 22 June panel discussion organized by the Spirit in Education Movement (SEM) for World Refugee Day, HardStories journalist Nicha Wachpanich said that she found at least 129 posts and comments on social media containing hate speech towards migrants from Myanmar between August 2024 – February 2025, and that online hate has led to harassment against migrant workers.

Nicha is part of a team that published “How a hashtag made Myanmar migrants the enemy,” an investigative report on fake news and hate speech against Myanmar migrants. She said that some forms of expression on social media have crossed the line of free speech and turned dehumanizing, using terms that compare migrants to animals or advocating that they should be killed.

Nicha noted that the hate against Myanmar migrants began with a TikTok video clip of migrant students at a learning centre in Surat Thani singing the Myanmar national anthem, which came under attack from netizens and led to the closure of several learning centres across the country. The Ministry of Labour has also formed a team to crackdown on undocumented workers. The social trend has become a tool for nationalist groups to build their own political platform, she said.

Shifting Target

With the rising tensions along the Thailand-Cambodia border, right-wing groups and their supporters have found a new target. Influencers began threatening violence against Cambodian migrant workers. Akkarawut posted on social media that his followers should send him information about Cambodian migrants who might be spies, and that he will hun down Cambodian migrants who are “taking jobs” from Thais. Members of right-wing groups have gone knocking on doors to ask if any Cambodian worker lives there. They have also reportedly gone into shops that employ migrants, demanding to know whether the owner is around and whether the employees have work permits.

Since early in the conflict, which began in May, the online threats of violence and racist sentiment have spread fear among the Cambodian community. Soon after the 28 May clash at the border in Chong Bok, a Thai user who is part of a right-wing extremist group threatened to attack Cambodians if any Thai soldiers got injured. He also encouraged Thai people to beat Cambodians, saying that they are “excellent punching bags” and posted that people should attack Cambodians because a Thai flag was stepped on. These threats caused Cambodian migrants to become concerned for their safety.

When three Cambodian workers were attacked in late July, some netizens said the workers were “asking for it” and “deserved it,” while others said that people should not incite racist hatred, but only if the migrants don’t cause problems.

Without any concrete measures to protect them, a large number of Cambodian migrants have left Thailand. It is expected that some sectors of the Thai economy, which rely heavily on migrants for their workforce, will take a hit if the workers leave and do not return.

Even humanitarian aid and welfare for Cambodian migrants become divisive. On Facebook, comments under Prachatai’s report that a hospital in Ubon Ratchathani had not refused to take in all Cambodian patients as previously alleged but only closed certain clinics expressed the sentiment that the hospital should not be taking Cambodian patients at all.

Some commented that Cambodian military spies could disguise themselves as patients, while others asked why a Thai hospital should help Cambodian patients when they had attacked Thailand and Thai patients are still waiting to be treated. One comment said that Thai soldiers injured during the border clash should be treated first if the hospital wants to treat Cambodian soldiers, while another asked if a patient’s relative can still hit Cambodians in the hospital.

Under a Thairath News tweet of a quote by exiled academic Pavin Chachavalpongpun urging the government not to cave in to a demand by a group of senators to cut the education budget for Cambodian migrant children, many netizens replied that Cambodians who receive welfare while living in Thailand are “ungrateful” and will turn around to attack Thailand, so they should not receive any support.

Senator Angkhana Neelapaijit, a former national human rights commissioner, spoke out against the demand. She said that children are not party to the conflict and, under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other humanitarian laws, must be protected during wartime. It would be a violation of children’s rights to subject them to racial discrimination or block their access to education and development. She has since been bombarded with online attacks, including an email accusing her of putting foreigners before Thai compatriots and demanding that she use her own money to cover education for Cambodian migrant children.

Meanwhile, netizens are making a variety of demands, from martial law, complete border closure, and the deportation of Cambodian migrants to a declaration of war and a military coup so that the military will have full power to handle the border dispute.