Prum Socheat throws a meditation pad on the floor of the Metta Forest pagoda and squats, flipping through photos collected from pagoda events. The lead monk acts as a school teacher reciting a story to his class, and on April 8, his class was two journalists.

The early photos are from community events: worshippers ceremonially washing a Buddha statue; visitors playing vai kor-orm, trying to smash a claypot while blindfolded for Khmer New Year; and residents constructing a small pond for the wild animals who pass through the pagoda boundaries. When the album reaches 2021, the photos take a dark turn: downed trees, a dead muntjac deer and people pointing out newly destroyed statues.

As he flips through pages of old Buddhist statues that graced the forested sanctuary, he starts an ad hoc chant in English: “Destroyed, we rebuild it, destroyed again.”

Just as the chant goes, residents of Trapaing Chor commune worry they will see destruction returning to their forest pagoda.

After a few years’ respite, the community around Kampong Speu’s Metta Forest say they fear military officials are preparing again to clear and dismantle what remains of the community forest and the unique pagoda within it.

The conflict restarted late last year, with some missing pots and kitchenware, residents told reporters.

On Dec. 28, some community members went out to ask soldiers if they had their cooking tools, but the conversation reportedly escalated to a fight, with soldiers detaining a man from the community for five days.

“We had to pay $5,000 to release him,” one elderly woman said, noting the community collectively contributed to the fund.

Since then, Trapaing Chor commune residents say they noticed military members clearing new patches of forest and planting cassava next to Venerable Socheat’s wooden hut, where he sleeps at night. Satellite imagery from the landscape, also known as Udom Sre Kpos forestry area, appears to show new fields created near the pagoda — though that is not nearly the same destruction as recorded in 2021 and 2022.

“We are worried every day that they destroy the pagoda and forests,” said 67-year-old Po Meas resident Chhoun Sam, who visited the pagoda to help the monks clean and clear brush. “We don’t want to lose it, that is why we keep trying to protect it.”

New Neighbors

Metta Forest may not have official status as a community protected area, but before the military intrusion, it was one in effect.

Socheat established the pagoda within a small patch of forest on the edge of Aoral Wildlife Sanctuary, in 2003, with approval from Kampong Speu provincial environment authorities, according to documents he showed to reporters. The pagoda’s presence brought some 200 families in Trapaing Chor commune close to nature and engaged in its protection, patrolling for small scale loggers, trappers and building projects like a pond where animals can come to drink water.

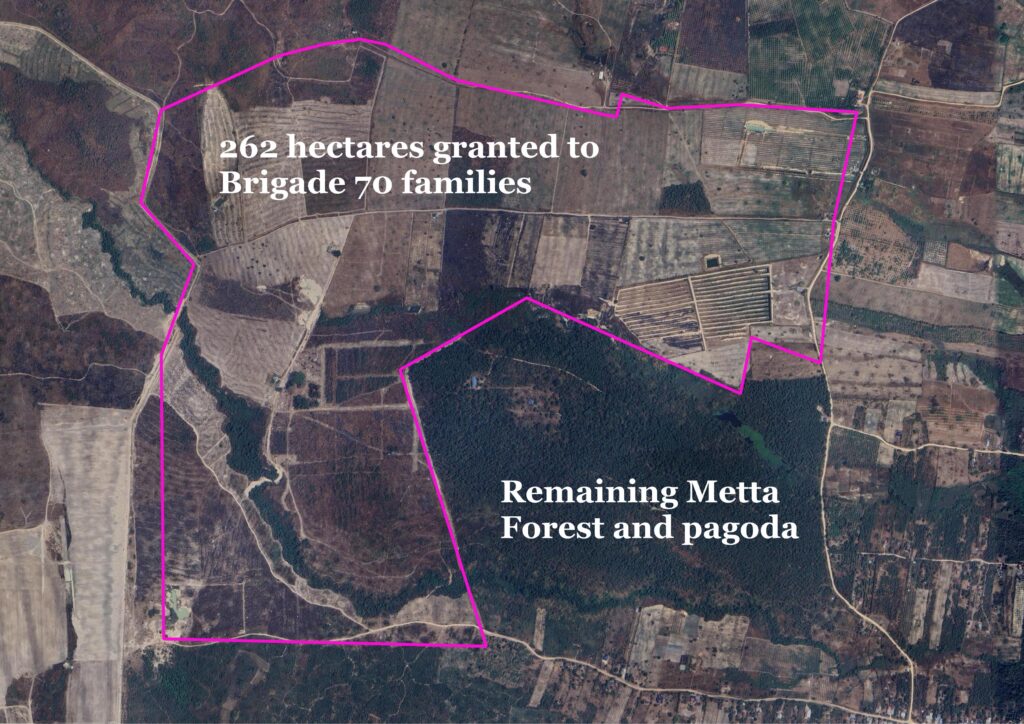

Then, in 2021, the government granted 262 hectares of this area to the Brigade 70 infantry unit, a division of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces that historically served as a bodyguard unit for former Prime Minister Hun Sen. More than 600 people protested the military occupation of the forest in 2021, and soldiers beat and shot at protestors, while burning down structures in the pagoda’s territory.

By 2022, the military appeared to clear the entire forest area, even going an estimated 20 hectares beyond the decree’s perimeter, according to satellite imagery analyzed by news outlet VOD.

After most of the trees were gone, soldiers built small houses surrounding one wide-trunked bodhi tree, where a decapitated Buddha statue sits, originally built for the pagoda. Villagers say they usually stay away from the soldiers’ homes, but on the clearing’s edge, they maintain a small patch of seedlings and a few solar panels on the edge of the clearing, signaling their intent to protect — and even expand — what’s left of the forest.

Several Po Meas villagers were criminally charged in 2021 and 2022 in the Kampong Speu Provincial Court over the dispute. Trials for at least five people are still ongoing until now – most recently delayed again in the latest hearing in March, according to local news outlet Phnom Penh Post – but community members say that there were actually 15 or 16 people with charges against them.

Tin Sochetra, a prosecutor at the Kampong Speu Provincial Court said the charges against these communities were filed because in October 2021, members of the communities allegedly insulted and intentionally harmed Pen Sarith, who represented the 40 soldiers’ families who benefitted from the land redistribution. Sochetra did not answer questions about the status of this case.

Residents say the soldiers were mostly inactive between 2022 and 2024, following the release of a letter from then deputy prime minister Sar Kheng, who called for the military to stop clearing Metta Forest.

That peace appears to be over, residents say. Khon Sarith, a farmer in Po Meas and advocate for the pagoda, said that ahead of the confrontation on Dec. 28, residents noticed that some of the possessions they left outside their homes were disappearing — which had never happened before.

“We can’t say that the military stole our stuff, but who else would dare to steal our stuff?” he asked.

Boeng Khmao, 42, said that he didn’t originally confront soldiers about the case, but he came to defend his wife and other women when soldiers allegedly chased them away with knives and sticks. Khmao said he was carrying a knife and in defending himself and his wife, injured one of the soldiers on the leg. He said he was detained after for roughly a week, until the community paid for his release.

“I am still afraid that I could have a problem with them again,” he said. “In addition, there is no transparency, they could be violent to us, but we can’t do that.”

Sarith said that the community is now afraid to confront the soldiers again, as they begin to clear forest closer to the pagoda and plant cassava in that space, far from the houses they built.

“Now, we can’t do anything better than to petition the Ministry of Religion,” Sarith said, noting that Wat Metta is an official pagoda. “Before, we put petitions to the ministries or [Kampong Speu] provincial hall, but there was no success.”

‘This is just the world’

When reporters arrived at the Metta Forest pagoda in April, they first walked into the freshly cut land: thin tree trunks ripped at their bases, the bite marks still freshly white. Then reporters noticed small fires and walked over to them — these were started by the community, clearing brush in the pagoda grounds before Khmer New Year festivities.

A group of 30 villagers still regularly gather at the pagoda to take care of the space, and discuss their plans to protect the pagoda.

Long Sokhthet, a 65-year-old member of this ad hoc committee, says they are wondering who to lobby next. Within this year, Sokhthet said a deputy provincial governor visited the forest, but he did not tell his name to community members. The official didn’t listen to residents’ concerns about the new clearings and cassava farm, Sokhthet said.

Kampong Speu’s provincial governor Cheam Chan did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Residents are trying to continue their replanting efforts and maintaining the forest, but Sokhthet said she doesn’t know how long they’ll be able to continue.

“We have replanted baby trees again and again, but the military destroys them,” he said. “The clearing land is bigger than before. They are almost encroaching our community’s [household] land.”

Chhoun Thea, 48, said younger residents had stopped participating in protests to protect the forest.

As the forest shrinks, residents are having more violent run-ins with the few wild animals left, said Venerable Socheat. The monk, who goes by the nickname Thomacheat, or “nature,” coos to the gibbons and macaques and offers sweet bananas and wedges of watermelon. Socheat refers to the animals as friends, but he adds that there had been a few incidents among friends lately. One of the gibbons bit a friendly dog the weekend before reporters’ visit, while a boar recently stabbed one of the Po Meas community members in the stomach.

The military are not as easy for Socheat to befriend, he said. Some of the soldiers ask him for forgiveness, seemingly because of his stature as a monk, and then promise to pay him off with the money they will earn from the investors. Socheat refuses their proposals, but still offers hospitality at the meditation center.

“I share my food with the soldiers when they come here,” Socheat says, and adds: “The community doesn’t like that.”

Despite the fear, the monks and community continue their meetings, recast Buddha statues, and nurture their saplings to plant again.

“We are a community that won’t let them take our land,” said Chhoun Sam. “They can control their own area.”

When asked if Socheat feels anything when soldiers destroy the Buddha statues, he replies quickly.

“This is just the world. The monk understands the way of Dharma.”

Socheat — who was a cofounder and then a key voice in dissolving legal status of the environmental activist group Mother Nature Cambodia — is well known among forest-dwelling communities. As the forest shrinks around him, he said communities in Preah Vihear, Kratie, Stung Treng and beyond call him to start a new temple in the woods.

The soldiers also signal for Socheat to leave, in a different way: at the end of April they knocked over a small stilted house, recently built for monks by the community members, into a pile of scrap.

Nevertheless, Socheat will wait. “There is a little forest remaining. When it’s all gone, I will think about it again.”

This article is published as Creative Commons.